Released in 1984

Original price: $2,500

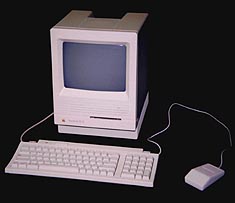

Apple Macintosh SE

Apple Macintosh SEFrom the Museum Collection |

Two months later, the Apple Macintosh arrived on the scene and some would argue that it did indeed change the arena of the personal computer forever with a simple two-word tag -- user-friendly.

Based on a radically different interface, the graphical user interface or GUI, the Macintosh featured a mouse-based system that incorporated pull-down menus in a window shade format -- instead of typing in arcane commands or choosing from a menu list of options, you pointed your mouse and clicked on different icons to accomplish tasks such as opening files, moving files or lauching applications. The reality-based icons borrowed from the office environment -- folders, documents, stacks of papers and a trash can in which to throw things away. The keyboard was basic with no command or cursor keys so that the mouse would have to be used as designed.

Steve Jobs, an engineer and company founder, oversaw the creation of the Macintosh, a descendant of the over-priced and underpowered Lisa computer. Jobs had been kicked off the Lisa production team for ruffling a few feathers and not being a good project manager. He took over the Macintosh program already being built by Jef Raskin. Raskin had been a frequent visitor to Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) and Jobs along with others at Apple had also seen a demonstration of PARCıs Xerox Alto workstation, which was the first production computer to be built around a graphical user interface.

While the Alto had come first, followed by the Lisa, the Apple Macintosh was the first commercially successful computer to use the GUI. Part of what made it work so well was Jobs' arguably single-minded attention to detail that actually drove Raskin from the project. Jobs wanted the Macintosh to be "friendly" -- not only in use, but in looks. Itıs face-like appearance -- with the display monitor over the disk drive -- was no accident. And itıs closed architecture ensured that the machine would not be cloned, a practice IBM embraced, or be expandable, a marketing tool IBM used successfully.

Jobs' take on the Macintosh was that it should be simple, easy to set up and to use immediately. And while that objective was attained, the machine had obvious drawbacks. With only 128Kb of RAM and limited software to fit that format, the Macintosh was restricted in its use. Copying a disk proved to be a nightmare that required a number of disk changes. A second floppy or a hard drive would have solved the problem, but Jobs believed including them would drive the price too high.

The Macintosh initially sold well, but by the end of the year, sales plummeted as word traveled that the computer was woefully lacking in RAM and expandibility. IBM PC faithful referred to the Macintosh as a "toy," not a serious computer for businesses or the home user.

In 1985, Jobs left Apple abruptly after a heated argument with president and CEO John Sculley, who was brought into the company by Jobs in 1984. Despite his untimely departure, Apple continued to develop "user-friendly" computers and improve on the areas where the Macintosh had been lacking. The creation of the LaserWriter, the first laser printer for the home computer user, inadvertently created a niche market in desktop publishing. The ease of the system and the what-you-see-is-what-you-get features of programs like Microsoft Word (first introduced on the Mac) and PageMaker helped Macs replace the archaic typesetting machines of years past.

By the early '90s, it was clear that the Motorola 680X0 line of CPUs was reaching the limits of its abilities. Apple then teamed up with IBM and Motorola on a next-generation family of CPUs for the Macs. Dubbed the PowerPC, the new CPU took the Mac into the 32- and 64-bit realm of computing.

But even with the new PowerPC-powered Macs, sales continued to slump. A brief flirtation with licensing other companies to make Mac clones didn't boost sales or the amount of third-party software, either.

In 1996, Apple purchased Steve Jobs' NeXT computer company, and Jobs was reinstalled as Apple CEO. Almost immediately, Jobs began redesigning the Mac. The result was the sleek iMac. As with the NeXT, the iMac had no floppy drive. And in a bit of consumer marketing genius, Jobs had the iMac available in a variety of fruit-themed colors -- names like tangerine and blueberry. iMac sales were phenemenol, with hundreds of thousands pre-ordered before the new computers were even released. For the first time in years, Apple began to regain market share, and became -- again -- the No. 1 computer manufacturer in the world.